Every structure, from a humble garden shed to a soaring skyscraper, relies on one critical element for its stability and longevity and that is the foundation. This decision involves selecting the appropriate Types of Building Foundations for the specific site conditions and structural load.

Often unseen, the foundation is the structural bridge that transfers the building’s weight safely into the earth. It prevents the building from settling unevenly, shifting, or collapsing.

Choosing the right type of foundation isn’t a one-size-fits-all decision; it’s a careful calculation based on two main factors: the weight and nature of the structure (the load) and the strength and composition of the soil beneath it (the bearing capacity).

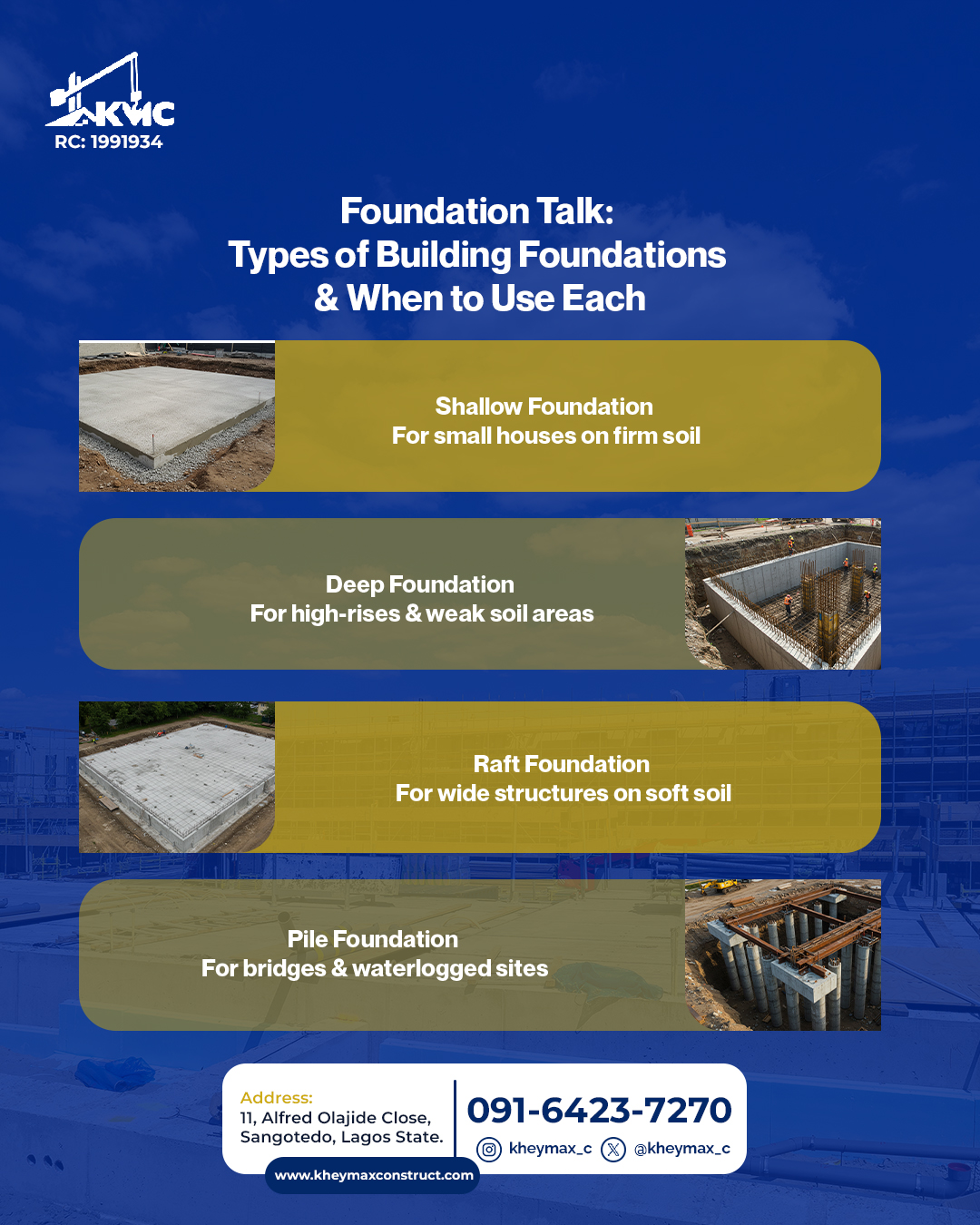

Foundations are broadly classified into two main categories: Shallow Foundations and Deep Foundations.

1. Shallow Foundations

The Most Common Types of Building Foundations for Residential Homes

As the name suggests, shallow foundations are constructed close to the ground’s surface. They are used when the soil layers right beneath the structure have sufficient bearing capacity to support the load.

Generally, they are considered “shallow” when the depth of the foundation is less than its width and typically less than 3 meters (10 feet).

Shallow foundations are the go-to choice for lighter structures like residential homes, small commercial buildings, and areas with stable, competent topsoil. They are typically more economical and faster to construct.

Types of Shallow Foundations and Their Uses

| Type of Foundation | Description | When to Use It |

| Spread Footing (Isolated/Pad Footing) | A square, rectangular, or circular pad of concrete that supports a single column. |

Most common and economical. Used when the load is transferred through individual columns, typically for ordinary light-to-medium-weight buildings.

Strip Footing (Wall Footing)

A continuous strip of concrete, wider than the wall it supports, running beneath load-bearing walls.

Ideal for structures where the load is carried by load-bearing walls instead of columns (like older masonry buildings) or to support a row of closely spaced columns.

Slab-on-Grade Foundation

A single layer of concrete slab poured directly onto prepared soil. The edges are often thickened to act as an integral footing.

Best for warm climates where the ground doesn’t freeze (to avoid frost heave). It’s a quick, low-cost option for single-story homes, garages, and driveways.

Raft or Mat Foundation

A large, continuous concrete slab that covers the entire footprint of the building, supporting all columns and walls.

Used when the soil has very poor bearing capacity or when the columns are so closely spaced that individual footings would overlap.

It spreads the total load over the largest possible area, like a “raft” floating on the weak soil.

2. Deep Foundations: Reaching the Strong Stuff

Deep foundations are employed when the soil near the surface is weak, highly compressible, or unstable and cannot safely support the structure’s load.

These foundations extend far below the ground surface, transferring the load to much deeper, stronger, more stable soil strata or bedrock.

They are essential for heavy, concentrated loads from large structures like skyscrapers, high-rise apartments, bridges, and industrial plants.

While more costly and complex, deep foundations provide superior stability in challenging soil conditions.

Types of Deep Foundations and Their Uses

| Type of Foundation | Description | When to Use It |

| Pile Foundation | Long, slender columns of steel, concrete, or timber that are driven or drilled deep into the ground. They transfer the load through end-bearing (resting on rock) or skin friction (adhesion with the surrounding soil). | Necessary when the strong soil or bedrock is far below the surface (e.g., in marshy land, soft clay, or sites near water). Used extensively for bridges, tall buildings, and structures in liquefaction-prone areas. |

| Pier Foundation (Drilled Shafts/Caissons) | Similar to piles but typically larger in diameter. A hole is drilled and then filled with reinforced concrete. | Used when the strong soil or bedrock is at a moderately deep level (between 10m to 100m) and the load is too high for smaller piles. They are easier to construct in varying ground conditions than driven piles. |

| Caisson Foundation (Open Caissons) | Large, watertight hollow structures (often cylindrical) sunk into the ground or water, then filled with concrete to form a solid foundation. | Ideal for foundation construction underwater (bridge piers, marine structures) or when excavating very deep through soft, wet soil layers. |

Choosing Your Foundation: The Critical Factors

The selection of the foundation type is the single most important decision in any major construction project, typically handled by a professional geotechnical engineer. Here’s a breakdown of the key factors that drive the final choice:

Soil Conditions (Geotechnical Report)

This is the most critical factor. A geotechnical report provides a detailed analysis of the soil’s composition, strength, and groundwater levels.

- Strong, stable soil near the surface: Likely calls for a Shallow Foundation (e.g., Spread Footings or Strip Footings).

- Weak, compressible, or expansive soil near the surface: Requires a foundation that bypasses the weak layer, leading to a Deep Foundation (Piles or Piers) or a widely distributed load system like a Mat Foundation.

- High Water Table or Freezing Climates: Foundations must be set below the frost line to prevent damage from frost heave (the expansion of freezing water in the soil). This may necessitate deeper footings or a Frost-Protected Shallow Foundation (FPSF).

Structural Load and Type

The size and weight of the building dictate the necessary bearing capacity.

- Light, Low-Rise Structures (Homes, Sheds): Shallow Foundations are almost always adequate and preferred for cost.

- Heavy, High-Rise Structures (Skyscrapers, Industrial): These structures exert massive concentrated loads that almost always require Deep Foundations (Piles, Piers) to ensure stability and minimize settlement.

Cost and Time Constraints

The budget and schedule heavily influence the choice.

- Shallow Foundations are significantly less expensive and faster to construct as they require less excavation and specialized equipment.

- Deep Foundations involve complex machinery, specialized labor, and more materials, making them a much higher investment in both time and money. They are only chosen when the site conditions leave no other safe alternative.

Conclusion – Start with the Ground Up

A building is only as strong as what it sits on. The foundation is the essential, unsung hero of construction.

Never underestimate the importance of a thorough site investigation and a professional geotechnical engineering analysis before a single shovel hits the dirt.

The right foundation, tailored precisely to the structure and the ground beneath it, is the true bedrock of any successful, long-lasting construction project.